Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality but an escape from personality. But, of course, only those who have personality and emotion know what it means to want to escape from these.

—T. S. Eliot, Tradition and the Individual Talent, 1919

If you are looking for the freshest musical analysis of new rap records being written by stuck-in-the-Nineties, bookish, 50-something white guys, then I have it on good authority that Rolling Stone still exists, and, if I recall, it specializes in that kind of thing. Go poke around, and I’m sure you’ll find something. I’ll note here only that the new Kendrick Lamar album, GNX, sounds pretty good to me, and it is, I confidently predict, the sort of thing you’ll like if you like that sort of thing. About hip-hop in 2024 per se I do not have very much to offer. I can say this much: As a matter of technical verse composition, Lamar is very, very skillful and inventive; instrumentally, his musical universe is rich, complex, and unpredictable. Also, GNX is named after a terrifically fun car, one of the few great exemplars of Reagan-era American automotive muscle and very possibly the last Buick that anybody would describe as “badass.”

So, that’s that.

I do have some thoughts about all the God stuff.

Lamar’s journey from more or less recognizable Christianity through Eckhart Tolle to whatever pit of New Age goo he has landed in has produced (the critics seem nearly unanimous here) some very interesting music. As a spiritual journey, Lamar’s arc is pure Americana—and it would be characterized as heresy if it were a bit more intellectually developed and if we lived in a society that still took that sort of thing seriously.

I deserve it all.

Keep my name by the world leaders

Keep my crowds loud inside Ibiza.I deserve it all:

More money, more power, more freedom,

Everything Heaven allowed us, bitch,I deserve it all.

…

A close relationship with God,

Whisper to me every time I close my eyes.

He say, “You deserve it all.”

It may not be Joel Osteen exactly, but the private jets and all that stuff—that’s God’s will, we are to believe, an earthly reward presaging the supernatural one. I myself am agnostic on that point, but it is worth taking note of the fact that this is a variant of the so-called “prosperity gospel.” Kendrick Lamar is nothing if not all-American, offering himself up as a one-man city on a hill. Maybe he has been reading John Winthrop: “The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.”

The lyrics quoted above are from “The Man at the Garden,” in which Lamar lists all of the things he deserves and all of the benefices justified by his musical ministry, a litany so absurd and silly and self-aggrandizing that, on first listening to it, I assumed it would take a sudden self-deprecating turn, which would be in keeping with the often self-critical character of Lamar’s lyrics. Nope. Lamar is in full-on pseudochristos mode, offering himself up as a kind of pop-music messiah, a figure of geopolitical importance, a prophet (bluntly declaring on another track, “I’m prophetic”), a suffering servant of the people, resisting temptation, all the rest of it, the whole messianic enchilada. He presents himself simultaneously as Lucifer and as the Son of God, these being, in his telling (and he assumes the voice of God to tell it) only different iterations of the same underlying personality: his.

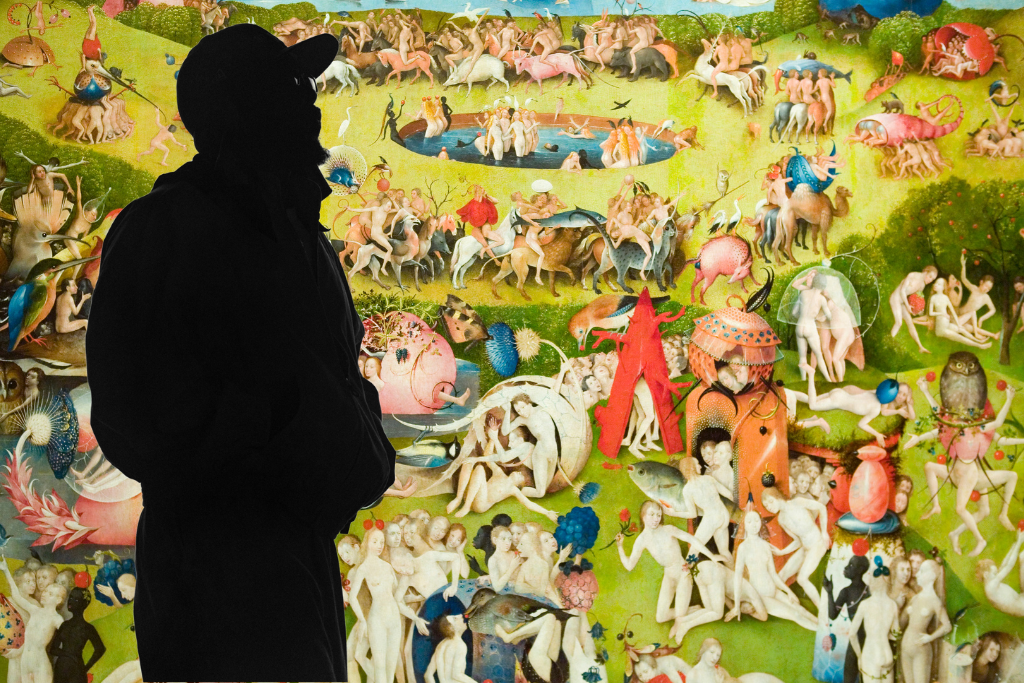

Lucifer—“Lucy” to Lamar—is a recurring character in Lamar’s work, and now the adversary is to be understood as simply another facet of Lamar’s artistic persona. That is a rather less interesting idea than the traditional one is, and, setting aside the specifically religious questions for a moment, it never seems to occur to any artist aspiring to greatness and a more catholic scope of relevance that there are excellent reasons the Middle Ages produced so much great art and literature while the New Age goo of our merely middle-aged civilization has produced very little that is of enduring interest. Lamar might have done himself a favor to spend less time with the works of Tolle and more with those of Hieronymus Bosch or Dante. There’s a lot of men-as-gods stuff in there and similarly loopy stuff, which is a departure for a lyricist whose earlier work was so plainly and explicitly Christian, if not always orthodox. Imagining that one has a direct line to the Almighty and can avail oneself of peace on the cheap may be comforting, but it is in most cases an artistic dead end.

The rapper’s sentiments as expressed are, as you might expect, much more powerful with the music. Nothing lets the air out of rap lyrics—or rock lyrics, or country lyrics, or almost any pop-music lyrics—like writing them out and hanging them out there on the page, naked, bereft of beat. Consider this representative run from “DNA” on Lamar’s acclaimed DAMN album:

I was born like this.

Since one like this, immaculate conception.

I transform like this, perform like this.Was Yeshua new weapon?

I don’t contemplate, I meditate.

Then off your, off your f—ing head.

This that put-the-kids-to-bed.

This that I got, I got, I got, I got

Realness, I just kill shit ’cause it’s in my DNA.

I got millions, I got riches buildin’ in my DNA.

I got dark, I got evil that rot inside my DNA.

I got off, I got troublesome heart inside my DNA.

I just win again, then, win again like Wimbledon I serve.

I am not at all convinced all those words add up to very much of anything that matters, but Kendrick Lamar was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music for the album. Who knows? Maybe Lamar is getting teed up for the Templeton prize for religious works.

Of course, it wouldn’t be fair to hold a hip-hop album up to the standards of systematic theology, but Lamar invites the scrutiny—demands it, even. There isn’t any reason to take Lamar seriously as a religious thinker or critic, but that isn’t stopping him, and while listeners are submerged in his world there is no avoiding the issue. There isn’t any real point in trying to impose some kind of religious or intellectual coherence on the material, which will resist, robustly, any such effort. But it is worth digging in to try to get a read on the religious sensibility at play here, which is idiosyncratic and Lamar’s exclusively but which also touches something in a broader slice of American popular culture.

What it touches is delusion. Being compelled, as we Americans seem to be, to pathologize and medicalize every social phenomenon, it is tempting to call what’s at work here narcissism. But psychiatric terms are meant for troubled minds, and there is not much reason to believe that we are encountering one of those here. What Kendrick Lamar has is a highly creative mind processing a sick culture—and what Lamar’s sensibility and the culture have in common is that both lack the tools to deal in a rigorous way with the issues at hand and the tensions the rapper senses without quite being able to get his head around them. Lamar is in desperate need of T. S. Eliot’s escape from emotion and personality—he suffers from a suffocating excess of both.

But that is an occupational hazard for would-be messiahs. The Protestant emphasis on a personal relationship with God has its merits, to be sure, but it also is an invitation to make oneself the center of the universe. Kendrick Lamar has a powerful imagination, and he is a gifted storyteller—limited by his inability to comprehend that there are stories that are not about him. For Lamar, whether the subject is Lucifer or God or some unnamed guitarist rising to fame in the 1940s (many listeners assume that the unspoken name is that of John Lee Hooker), every Kendrick Lamar character is Kendrick Lamar. He seems to take the idea of reincarnation seriously—“I did past life regression last year and it f—d me up,” he reports on “Reincarnated,” and at one point suggests that he may have had a hand in building the pyramids—and I suppose that it must be the case that, having achieved a very high degree of self-importance, hell really is other people.

Listen with a little bit of attention to Kendrick Lamar’s new album, and you might detect the influence of Clarence 13X, founder of a Nation of Islam offshoot known as Five-Percent Nation, who taught that black people constitute a nation of “gods and earths,” and whose views have wide currency in the rap world. Well. Listen a little harder, though, and you’ll detect the old familiar voice behind the voice: Frank Sinatra singing “My Way.”

“My Way” ought to be understood as the real American national anthem.

The self-importance of American celebrities (and of ordinary Americans, too) is a genuinely perplexing phenomenon, one that we seldom think about or acknowledge, probably because we never have known a world uncolored by that delusion. And that delusion has been with us since the beginning, when John Winthrop insisted that New England was to be that biblical city upon a hill, that “the eyes of all people are upon us,” he was talking through his buckled pilgrim hat.

In 1630, the eyes of all people were on anything but a band of hardscrabble separatist fanatics trying to pick a living out of the rocky soil of Massachusetts. But the pilgrims did not think of themselves as a gaggle of cantankerous-crackpot-irreconcilable -malcontents enduring a self-imposed exile; they thought of themselves as the new Israelites, a conceit that Americans ranging from conservative white Protestants to black-nationalist radicals have cleaved to ever since. Americans do not have a great talent for comedies of manners (Three’s Company!) or baroque domestic drama—Americans do thunder, and, specifically, we do one-man-against stories: one man against society, one man against nature, one man against God. (Moby-Dick is all three rolled into one.) The lonely hero, armed only with his virtue, is practically the only kind of character whose story we still know how to tell—and if the protagonist has to be Taylor Swift or Dave Chappelle or Frank Sinatra, then that’s still how the story is going to go.

The notion of pop musicians as world-conquering heroes and champions of perdurance is entirely ridiculous, but it is our great celebrity master narrative: “Look what I overcame to become rich and famous,” “Look what I have had to go through as a result of being rich and famous,” “Look upon my royalties, ye mighty, and despair.” Never mind that those at the commanding heights of American entertainment resemble those at our other commanding cultural and economic heights in being disproportionately (though of course by no means exclusively) drawn from the comfortable classes and that the Horatio Alger story is more the exception than the rule in Hollywood and Nashville just as much as in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. (The fanciest prep school in Santa Monica counts among its alumni Gwyneth Paltrow, Jack Black, Liv Tyler, Michael Bay, Zooey Deschanel, and Kate Hudson, those being the children of a Tony- and Emmy-winning actress and her television-producer husband, an Apollo project engineer, the singer from Aerosmith, a psychiatrist, a six-time Academy Award nominee, and Goldie Hawn.) Kendrick Lamar actually did have to overcome some pretty grimy childhood circumstances to get to where he is, but his tales of triumph on GNX aren’t really about that—they are about rap feuds and haters on social media and similarly banal discomforts.

How strange it is that we accept—uncritically—the celebrity’s insistence that being a celebrity is a hard row to hoe. That sort of thing works—as marketing and as content—only because we participate in the delusion. Sometimes, that participation has to be gently induced: Rap feuds, like celebrity romances and rehab tell-alls, are pure kayfabe, a way of bringing the fake wrestling match out of the ring and closer to the fans. (Yes, I am aware that people have been killed in these feuds; that doesn’t mean that they aren’t marketing strategies, which they are.) Imagine the scale and the depth of the shared delusion it took for Frank Sinatra, a man with 60 tuxedos in his closet who hadn’t lifted anything heavier than a ukelele since he was a teenager, to sing those lyrics by Paul Anka—and for audiences to tear up instead of laughing their asses off:

Yes, there were times, I’m sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew.

But through it all, when there was doubt

I ate it up and spit it out.

I faced it all, and I stood tall

And did it my way.…

For what is a man, what has he got?

If not himself, then he has naught.

To say the things he truly feels

And not the words of one who kneels.

The record shows I took the blows

And did it my way.

Sid Vicious did not have to change very much to make a joke out of “My Way.” He just sang it while being Sid Vicious. It is never enough to be a “saloon singer,” as Sinatra used to call himself. The kind of adulation and wealth that goes along with being a modern American celebrity would be unseemly for someone who was merely a competent and popular entertainer—it would violate some kind of implicit national sumptuary law. And so that entertainer must be something more than an entertainer: He must be a figure of surpassing significance. Anybody who has ever known a professional performer knows that the Elizabethans were right to rank them socially with prostitutes and procurers rather than with the princes and bishops.

But it isn’t just popular singers. Think of every comedy special you’ve ever seen that began or ended with a gritty black-and-white (or grainy, VHS-style) montage rehearsing the artist’s struggles and the many obstacles he overcame. American celebrities all have a little Muhammad Ali in them, and they deal in superlatives: “I am the greatest.” (This is one of the ways you can tell that Donald Trump comes from the world of celebrity rather than the world of politics.) But it is a very strange hero’s journey: You make an album or a movie or a comedy special, then you make another one that gets very big, then you make a couple of artsy ones that don’t do as well, and then you make another one that makes you popular again, and then you … stage for yourself a kind of Roman triumph but with a budget and rhetorical flourishes and an outpouring of imperial grandeur that would have made Pompey blush. But those Romans showed the way. It wasn’t enough to be primus inter pares or pontifex maximus or imperator or even Augustus—eventually, you’re going to want to put up your statue in the temple alongside Jupiter and Mars. Eventually, you want to be a god.

And that is how you end up with Kendrick Lamar doing a duet with God, at one point.

It starts as a clever lyrical conceit. The rapper talks about his father kicking him out of the family home for rebellious behavior. As the song develops, it eventually becomes clear that we are not talking about an ordinary family home but the heavenly kingdom, from which Lamar-Lucifer has been expelled, losing his prior role as music director (there’s a lot of plot on this album) and being subjected to centuries of reincarnation—including as a tragic Billie Holiday-type figure who dies with a needle in her arm—until he learns his lesson about pride and willfulness.

You fell out of heaven ’cause you was anxious.

Didn’t like authority, only searched to be heinous.

Isaiah fourteen was the only thing that was prevalent.

My greatest music director was you.

It was colors, it was pinks, it was reds, it was blues.

It was harmony and motion.

I sent you down to earth ’cause you was broken.

Rehabilitation not psychosis.

How much of that Five-Percenter stuff Lamar has ingested is not entirely clear, but there’s a fair bit of paganism to be found in his lyrics. As Lucifer, he writes that he was dispatched to Earth by God—and in his current incarnation (“My present life is Kendrick Lamar”) he was sent, as he reports, “by my ancestors.” God is reduced to a supporting role—He gets a verse, to be sure, but the subject is always Kendrick Lamar.

Hip-hop is the most distinctly American genre of modern music for reasons that are in the main non-musical: Its culture has been profoundly shaped by the computer and by entrepreneurship. The country that produced Steve Jobs was always going to be the country that produced Kendrick Lamar. And, of course, hip-hop is black music, and entrepreneurship comes naturally to black Americans, who were excluded from so much of the formal economy and the corporate world until the day before yesterday.

Americans are natural entrepreneurs, and that dynamic has always informed our national religious life, too. If there is a characteristically American religious institution, it is the start-up church—whether a storefront congregation in Philadelphia, a megachurch in the Atlanta suburbs, or a brand new religious movement cooked up ex nihilo by some spiritually inclined showman and founder. Consider the remarkable century of 1830 to 1930, which saw the founding of a dozen significant religious movements in the United States, several of which became major worldwide communions: Mormonism (1830), Seventh-day Adventism (1863), Theosophy (1875), Jehovah’s Witnesses (1876), Christian Science (1879), Black Hebrew Israelites (1886), Pentecostalism (1906), Rosicrucianism (1909), Moorish Science (1913), Reconstructionism Judaism (1923), and the Nation of Islam (1930). A shorter remarkable run from 1954 to 1967 begins with Scientology and ends with the Manson cult, with the years in between witnessing the emergence of the Peoples Temple, the Branch Davidians, the Universal Life Church, the Charismatic movement, Eckankar, and the Church of Satan.

As that sneaky little fellow said, “You shall be as gods.” And if the religion you have doesn’t put you on the throne, then you can start a new one. The first great cultural project of the American republic was the sanctification of the new American state through the deification George Washington, whose austere personage you can see depicted as Jupiter enthroned and in purple, surrounded by foreign gods (Minerva, Ceres, Neptune) and domestic demigods (Samuel Morse, Robert Morris, Benjamin Franklin), a scene painted on the inside of the Capitol dome by Constantino Brumidi, a painter whose main previous client had been the Vatican.

A people who will make a god out of a mere politician or an athlete or a singer will make a god out of anything or anybody—they are not a religiously serious people. The deification of presidents is mainly an expression of nationalism (the president, like the English monarch, is a sanctified national personification in which the polity worships itself, which, having been taken to an extreme, is the root cause of our current political distortion), while the deification of people who are famous or beautiful or very good at certain children’s games is old-fashioned pagan idolatry. “You shall be as gods”? It’s hardly a new idea. But it never has been a very good idea. RZA, another rapper influenced by Clarence 13X and that “gods and earths” stuff, offers an example of how wrong that can go and how quickly:

Since I’m known to be a student of the Five Percent, people know that I was taught that the white man is the Devil. But I believe people misunderstand the practical application of that wisdom. It relates to what Jesus said about the flesh being weak. Yes, I believe the white man has a nature he must contend with, and historically, that nature has been aggressive, violent, conquering, and prone to devilishment. But to me, there’s a simple explanation for that. If you have a birth record of six thousand years on a planet that’s trillions of years old, with people who’ve been here for millions of years longer than you, you’re a baby. You just need to grow up.

Setting aside the racism (which is, along with Kanye-style antisemitism, endemic in this stuff), consider that this is just . . . bananas. There is the matter of the actual record: Neither the Earth nor the universe in which it is situated is “trillions of years old,” and there are no people on Earth “who’ve been here for millions of years longer” than others, the species H. sap. having been uprightly walking around (on this approximately 4.54-billion-year-old planet) for something like 300,000 years, maybe a bit less. Is it notable how the supposedly scientifically minded among us can end up basing their worldviews on “facts” as silly and baseless as those relied upon by “young Earth” creationists. While it is true that the lighter skin tones associated with European populations are a relatively recent development in human evolution (probably about 8,000 years old), the notion that this has some kind of moral or spiritual significance is bizarre. It also is a lightly reworked version of the old white racist notion that Africans and other dark-skinned people are primitive in that they are more closely connected to our earlier hominid ancestors (and, hence, to the lesser apes) than they are to the supposed advanced races that inhabit Denmark or Sweden or Cumbria or wherever. You may as well be talking to Flat Earthers.

Spiritualizing ancestry is a fairly common religious and cultural practice across time and in many different places: the Hindu world in its way, Nazi Germany in its way, the Mayflower Society in its way. Spiritualizing the people as a whole, as a polity or as a cultural entity, is a common practice as well. Ancestor worship and religious nationalism tend to flare up in times of social change: There was no Mayflower Society until the late 19th century, when the abolition of slavery and mass migration complicated life for the supposedly Anglo-Saxon establishment. Other religious phenomena also interact with social change and political phenomena: The people we now know as the Methodists were a reform movement within the Church of England until the revolution ruptured ties with the mother church in England and forced John Wesley’s hand.

And maybe there is, in a sense, where we are now: A combination of factors ranging from social change to scientific skepticism to the breakdown of the family to the self-discrediting antics of so many conventional religious leaders in the United States (and beyond) have ruptured ties with the mother church—which is to say, with orthodoxy—for many millions of people, particularly for well-off and educated people without very strong religious ties or meaningful religious education, who happen to be the sort of people who set the tone for the popular culture as a whole.

In such a context, a brilliant and creative autodidact such as Kendrick Lamar is very likely to bounce from view to view and from posture to posture, ensorcelled by the last three sentences he read from Eckhart Tolle or Maya Angelou or some anonymous weirdo on the internet. We do, indeed, inhabit a garden of earthly delights, Kendrick Lamar’s “Man at the Garden” as much as Hieronymus Bosch. Digital delights, too. We can only offer Kendrick Lamar the same prayer that Thomas More made for his young friend with inconstant religious sympathies: “We must just pray that when your head’s finished turning, your face is to the front again.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.