The human rights lawyer Ramsey Clark, who has died aged 93, was a Texas maverick. Though he was at the forefront of the push for civil rights under President John F Kennedy and served as attorney general under President Lyndon Johnson, he went on to speak for unpopular causes and become a harsh critic of US policy.

He came from the heart of the the lone star state’s political establishment – as a child, he made ice cream in the kitchen of the future president’s wife, Lady Bird Johnson. But whereas his father went on from serving as attorney general to be a supreme court justice, the son moved to the edge of political respectability and –many believed – well beyond it.

In later life, Clark offered his legal services and political support to an outlandish horde of clients. They included Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic, Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, imprisoned for his involvement in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York, and David Koresh, the messiah of the Branch Davidian cult, brought to end at Waco, Texas, in the same year, as well as the American fascist Lyndon LaRouche and a number of other genocidal criminals, wild-eyed extremists of left and right and murderous misfits.

Naturally Clark’s motives were the subject of unsympathetic speculation. There was the puzzling fact of his closeness to a Marxist group on the bleaker fringes of the American left, the Workers World party, or “Marcyites”, after their leader, Sam Marcy. One critic shrugged that he was “a good man gone ga-ga, years ago”. None doubted his courage.

The most persuasive conclusion is that Clark believed passionately in justice and in everyone’s right to legal advice, however bad their record or dire their predicament. But many, even among those who could concede the generosity of his motives, felt obliged to add a rider: his judgment was terrible.

After his failure to obtain electoral office in the 1970s, his politics were sharply radicalised. “The US is not a democracy,” he told an Egyptian interviewer in 2003. “Most Americans do not vote. We haven’t had a real choice for a long, long time now. The US is a plutocracy.”

Born in Dallas, William Ramsey Clark was the son of Tom C Clark, a wealthy attorney appointed US attorney general (1945-49) by President Harry Truman, and his wife, Mary (nee Ramsey). After serving in the Marines (1945-46) Ramsey studied at the University of Texas, and gained a law degree at the University of Chicago. He practised law in his father’s firm in Texas for 10 years, and in 1961 was appointed an assistant US attorney general under Robert Kennedy. Formally, he was the head of the lands department, but he soon found himself involved in the civil rights struggle.

The Kennedy administration was sympathetic to civil rights. But it was also slow to risk political resentment by identifying too strongly with the movement. Clark found himself involved in many ways, for example as the senior civilian official on the ground after racist rioters tried to prevent James Meredith from registering as the first black student at the University of Mississippi in 1962.

When, after President Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, the Johnson administration came out unambiguously for civil rights, Clark played an important part in drafting the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act the following year. He was made uncomfortable by Martin Luther King Jr’s Poor People’s Campaign, when black protesters and their mules camped in Washington’s monumental Mall in 1968.

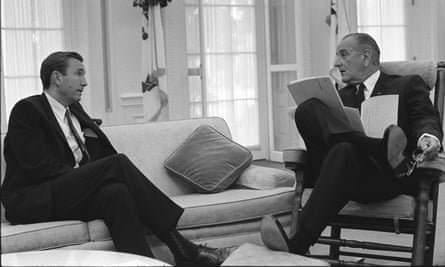

In 1967 President Johnson appointed Clark attorney general. The wily president calculated, correctly, that Ramsey’s father would have to resign from the supreme court to prevent a conflict of interest, thus freeing a seat for Johnson to appoint the first African American justice, Thurgood Marshall. But by the time the Johnson administration had run its course, Ramsey was disillusioned. He was fiercely opposed to the Vietnam war, though he still prosecuted anti-war protesters, including the celebrated paediatrician Benjamin Spock.

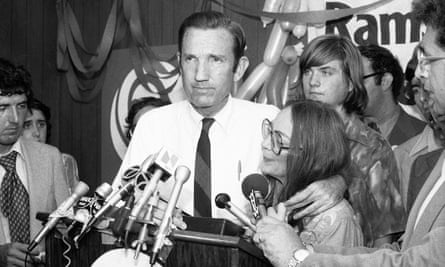

When Richard Nixon became president in 1969, Clark moved to New York, bought a flat in Greenwich Village and began to practise law. In 1974 he ran as the Democratic senatorial candidate for New York but did not unseat the Republican incumbent, Jacob Javits. In 1976 he ran again for the Democratic nomination, but was beaten by Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Bella Abzug. At that time he was seen as a centrist, certainly by comparison with the latter.

Giving up on mainstream politics altogether, Clark became involved with the World Workers party and an organisation, largely staffed by its members, called the International Action Center. In 1980 he travelled to Tehran for a conference on the “crimes of America”.

Over the years, Clark defended or attempted to defend – sometimes formally as a lawyer, sometimes politically – people accused of the gravest atrocities. At the international Rwanda tribunal in Tanzania (2001-03) he defended Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, the Rwandan pastor accused of inviting Tutsis to hide in his church, then summoning Hutus to massacre them during the genocide of 1994.

Because he defended two Baltic concentration camp guards and the Palestinian terrorists who threw the Jewish American Leon Klinghoffer into the sea in a wheelchair during the Achille Lauro hijacking of 1985, Clark was accused of anti-semitism, a charge he and those who knew him dismissed. He also defended both Milosevic and the Bosnian Serb commander, Radovan Karadjic, and the Liberian dictator, Charles Taylor. In 2004 he went to Baghdad to defend Saddam Hussein – and in 2007 was thrown out of the court that found Saddam guilty.

His many critics thought the common ground between these clients was their enmity towards America. To those who knew Clark, a more plausible connection was that they were all people who could find few other defenders. William Kunstler, for example, the civil rights lawyer, who worked with Clark after the 1971 Attica prison riot, near Buffalo, New York, called him “the voice of conscience in the American bar”. Nicholas Katzenbach, Clark’s predecessor as attorney general, called him a man of “absolute decency, total honesty and sincerity”. In 2008 the United Nations general assembly awarded him its human rights prize.

In 1949, he married Georgia Welch, a fellow student at Texas. She died in 2010, and their son, Thomas, died in 2014. He is survived by their daughter, Ronda, a sister, Mimi, and three granddaughters.

William Ramsey Clark, lawyer, born 18 December 1927; died 9 April 2021

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion