The biggest challenge in opening up a national museum about African American history? How to talk about slavery

After he was named director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture 11 years ago — before planning had begun for its 400,000-square foot bronze-colored building on the National Mall, when it still had to raise more than half its $540 million price tag, when it had not yet a single one of its 37,000 artifacts — director Lonnie G. Bunch III struggled with questions about the monumental endeavor.

How much did Americans want to confront slavery?

Should the museum be a home for African Americans on America’s “front lawn” — once surrounded by slave auctions — or a place to teach others, namely white Americans, about a history they may not fully understand?

Would it be a somber memorial to centuries of pain and death, or a celebration of the achievements of African Americans, who have persevered despite a system perpetually against them?

When the newest Smithsonian museum opens Sept. 24 with a dedication led by President Obama and attended by President George W. Bush, it will weave stories of despair together with those of triumph, packing more than 400 years of history into 105,000 square feet of exhibition space. The institution’s 19th museum, sitting atop 5 acres of the mall’s last remaining museum plot, opens at a time when race in America has returned to center stage as the country’s defining, polarizing point of debate.

It’s the most expensive, biggest museum devoted to people of African descent anywhere in the world, and that makes things complicated.

— Samuel Black, past president of the Association of African American Museums

Since Congress funded the museum in 2003, the nation’s first black president was elected, and the Black Lives Matter movement rose to prominence with protests over police shootings of black Americans. Polls show Americans more divided by race than they have been in years.

Towns and universities are grappling with the role slavery played in their founding histories; the Confederate flag has been removed from city halls and the South Carolina statehouse. Over the years, black Americans have risen to the top across key posts of American culture yet remain underrepresented in the country’s march toward prosperity.

It’s not the the climate that Bunch — a black man who previously led the Chicago History Museum and was the first history curator at the California African American Museum when it opened in Los Angeles in 1984 — expected.

But it’s one he’s trying to embrace.

“It was crucial to create a museum that would help Americans remember and confront” the country’s “tortured” past and present, said Bunch, who describes his goal as bringing out the “tension between moments of tears and moments of joy.”

It’s a tug that curators want viewers to feel of as they walk through the dimly lit, quiet underground corridors that house the museum’s history section.

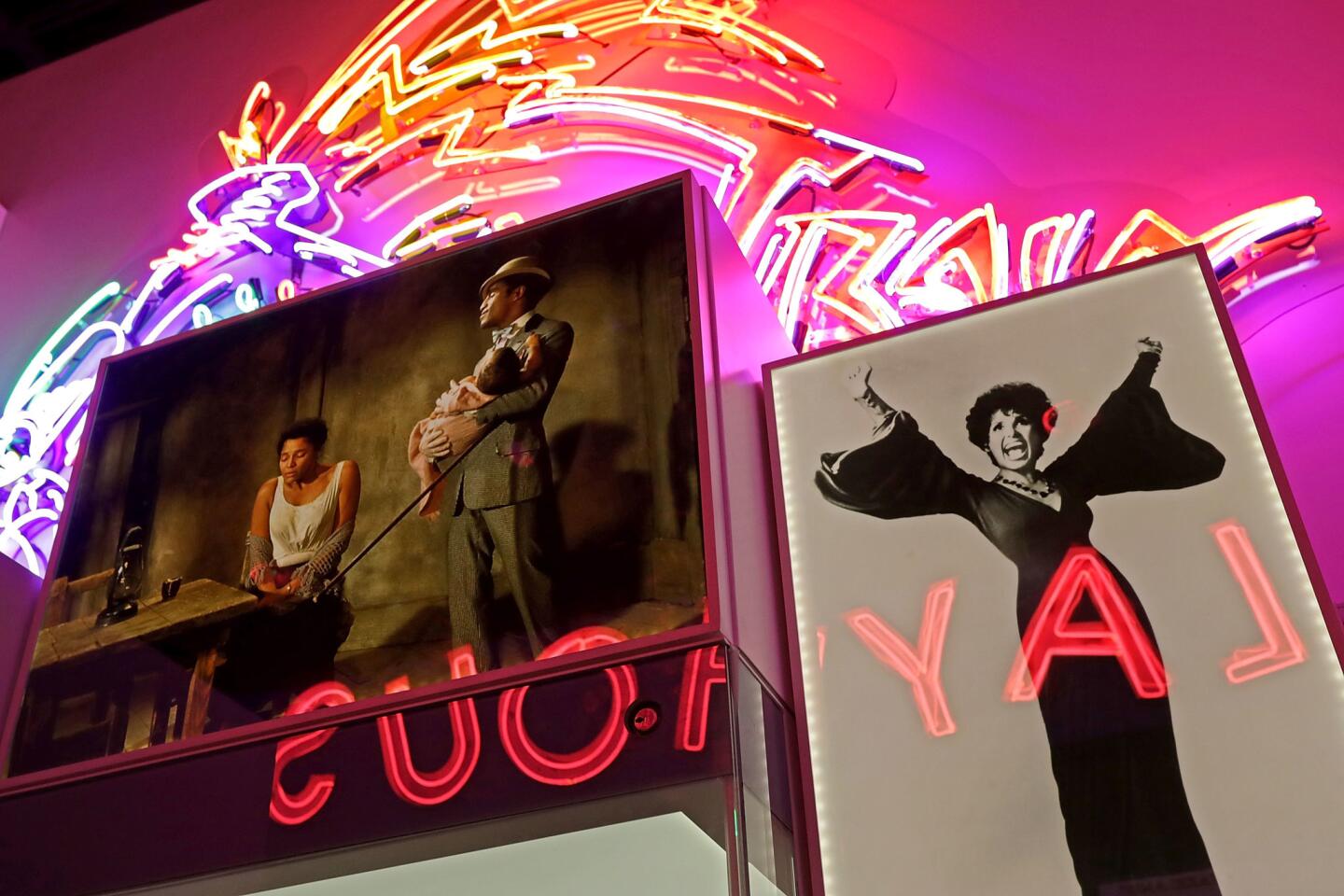

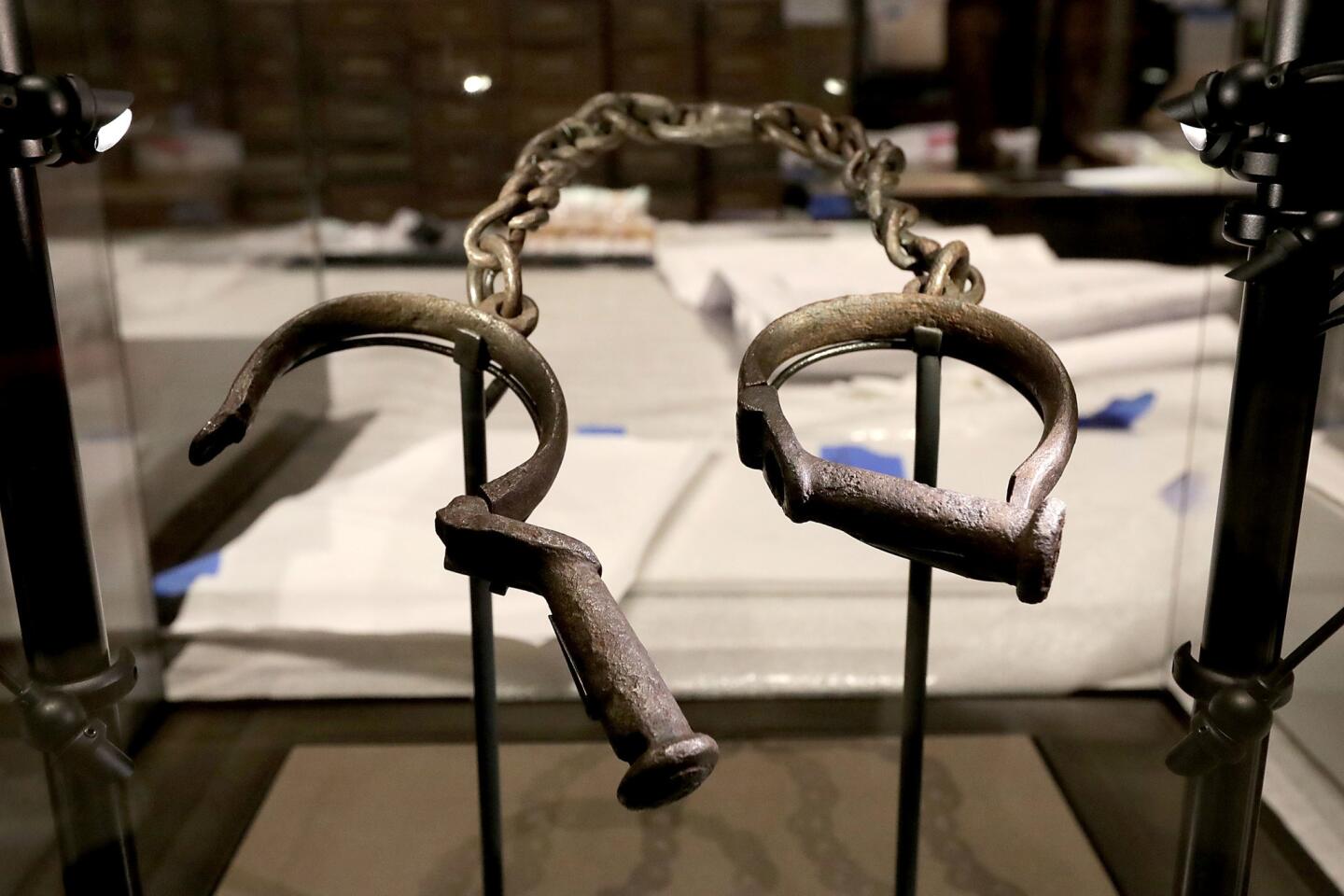

Here, Emmett Till’s casket is displayed feet away from Harriet Tubman’s lace shawl, rusted slaves’ shackles from Oprah Winfrey’s personal collection, and slave rebellion leader Nat Turner’s 19th-century pocket Bible. These mind-bending juxtapositions remain as visitors walk up to the museum’s brighter, louder upper “culture” floors, where Jackie Robinson, Richard Pryor, and Whitney Houston are celebrated alongside the Tuskegee Airmen and the 89 African Americans who have received the Medal of Honor since 1861.

“The African American is the quintessential American experience. It is the experience that helped us understand our notions of optimism, our notions of liberty, our notions of citizenship,” said Bunch.

He has sold the idea of the museum to donors and the public as one of the painful but rewarding endurance of what it means to be American.

The museum’s treatment of history is in part a response to market research. In surveys conducted during its planning, the Smithsonian found that Americans gave conflicting responses on slavery. It was the issue that potential visitors said was most important to explore — but the one they were the least eager to learn about.

To get around that squeamishness, the connection between past and present has been built into the chronology and design of the museum, which guides visitors from the bottom up, beginning with nods to pre-slavery, pre-colonial Africa before a full-throttled journey into the slave trade and the 12 million Africans shipped across the Atlantic.

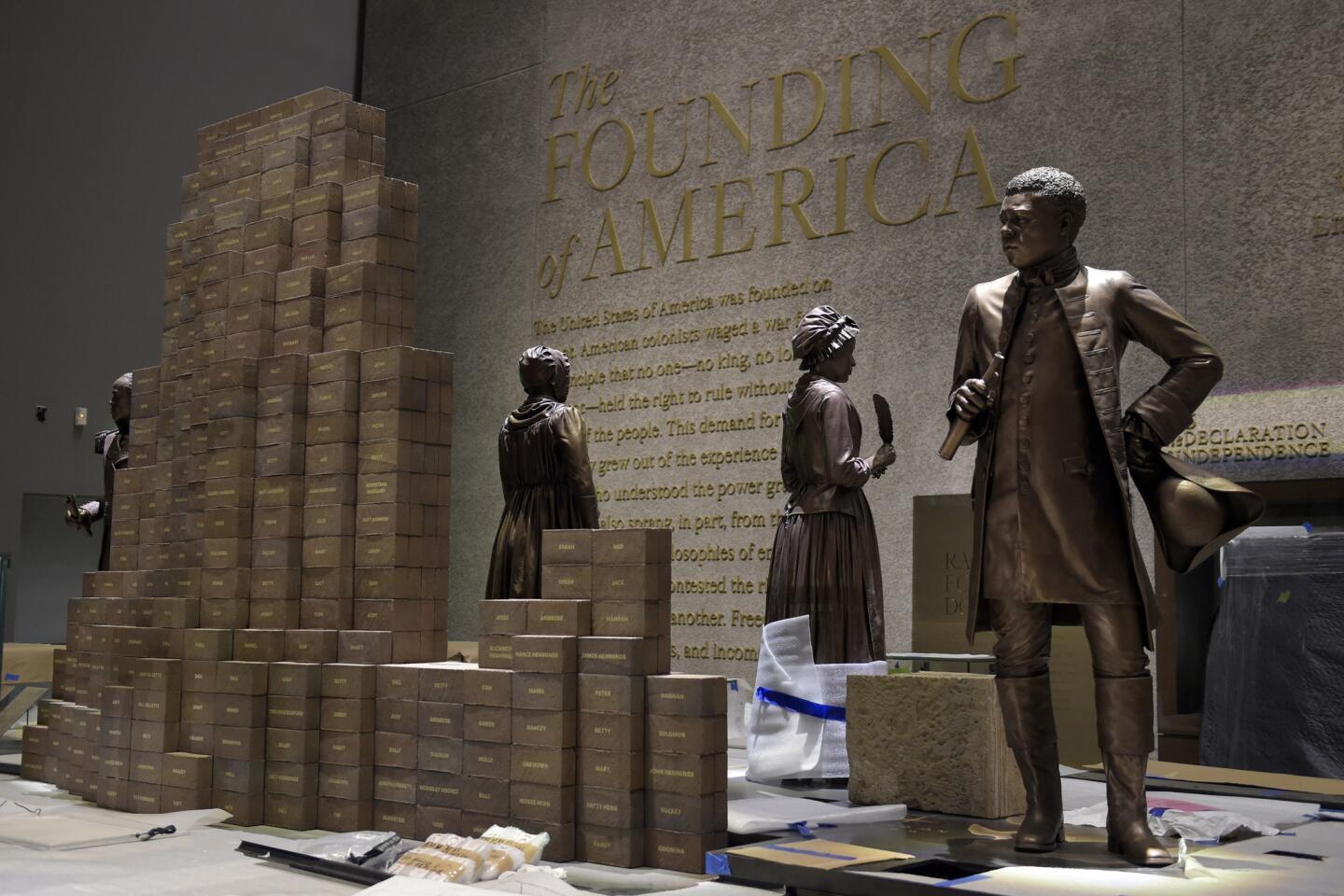

A statue of Thomas Jefferson standing in front of a stack of bricks with the names of his slaves is displayed next to the exhibition on how slaves fought on the front lines of the American Revolution. The floor ends with emancipation in 1863, leading visitors to the “Era of Segregation,” where they’ll encounter a stool from the 1960 Greensboro, N.C., Woolworth lunch counter sit-ins; the green and violet, floral-leaf patterned dress that Rosa Parks was sewing the day she was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Ala.; and dozens of relics from the then-budding Civil Rights Movement.

Black movements are connected to protests for gay rights, Latino rights and women’s rights.

On upper floors, an exhibit about slaves who worked in South Carolina’s 18th century rice fields sits aside a display of the birth of hip-hop in 1970s Bronx. A few steps away, a jail cell — measuring 6 feet 7 inches by 7 feet, 7½ inches by 7 feet, 8 inches — from the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, speaks of “slavery by another name,” and highlights the fact that blacks are more likely to be imprisoned than any other racial group.

Also on display are Chuck Berry’s red Cadillac convertible, Muhammad’s Ali’s boxing gloves and white robe, and a copy of Bill Cosby’s 1964 comedy record, “I Started Out as a Child.” Revelations of “alleged sexual misconduct have cast a shadow over Cosby’s entertainment career,” notes a description card.

“It’s the most expensive, biggest museum devoted to people of African descent anywhere in the world, and that makes things complicated,” said Samuel Black, the past president of the Association of African American Museums, who has watched as the proposal slowly made its way through legislative and budgetary defeats in the 1980s and 1990s. The idea was originally hatched 101 years ago by black Union Army veterans.

“You can’t cover everything of the black experience, and you’re always going to find someone who says something should be there or should not be there,” said Black, the director of African American programming at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

So Black Lives Matter, front-and-center in today’s debate on race and policing, makes just a cameo among close to 4,000 pieces shown. The movement is represented by a handful of protest photos, a TV clip that rotates through an appearance of one of the movement’s activists with Stephen Colbert, and a T-shirt and poster from demonstrations that followed the death of Trayvon Martin, the young man whose death in Florida at the hands of a community watch volunteer helped launch Black Lives Matter.

Far more astonishing is the relative lack of space devoted to the life of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Because King’s children have been caught in legal battles over the rights to his estate and tend to charge high licensing fees, the civil rights leader’s main appearance is in a small display devoted to the aftermath of his death, in a room on post-1968 social movements.

Obama, shown throughout the museum in photos, arguably has a stronger presence.

Curators, who culled materials from everyday Americans through an “Antiques Roadshow”-style tour and from major donors such as Winfrey, say they plan to regularly change what’s on display. They pointed to several theaters in the building where rotating films and presentations on historic and contemporary issues would allow it to stay current.

It’s a strategy that’s become common at modern museums, and one that many African American institutions face, said Alfred Brophy, a professor who researches the history of slavery and how it’s presented to the public at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “African American history is so nuanced and so packed, with everything from the extraordinary literature to the culture of brutality of slavery, that, good Lord, how do you convey it?”

That question, curators said, is one they are still grappling with, as displays are still under construction — and open to last-minute changes — before next Saturday’s reveal. That morning, Obama is scheduled to give a speech and ring a 500-pound bell on loan from a church founded by slaves and free blacks in 1776.

Simultaneously, churches across Washington will ring their own bells and museums, libraries and black cultural centers around the country will host viewing parties. They’ll need to: 28,000 free tickets for 15-minute windows of entry during the museum’s opening weekend were snapped up within an hour last month, and are not available until November after hundreds of thousands in total were booked through next month.

Jaweed Kaleem is The Times’ national race and justice correspondent. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

ALSO:

Why the exterior of D.C.’s soon-to-open African American museum is an exciting sign of what’s inside

What Georgetown’s atonement means for the campus debate over slavery

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.